Raphaela Vogel

Tränenmeer, 2019

Flatscreen, chromed steel tube, dog hair,

polyurethane elastomer, shower chair, speaker, amplifier,

Video: 19:21 Min.

Courtesy De Pont Museum, Tilburg

Puppenruhe, 2019

Aluminium trusses, chandelier, dolls

Courtesy the artist and BQ Berlin

Morgenstern, 2011‒2019

Acrylic on canvas, polyurethane elastomer

Courtesy Sammlung Anke and Frank Delenschke

Wizard, 2019

Surf sails

Courtesy he artist and BQ Berlin

Hijab Hund, 2019

Oil pencil, oil, varnish, leather glue on goat leather, polyester

Courtesy the artist and BQ Berlin

*1988, Nuremberg, Germany

Lives in Berlin, Germany

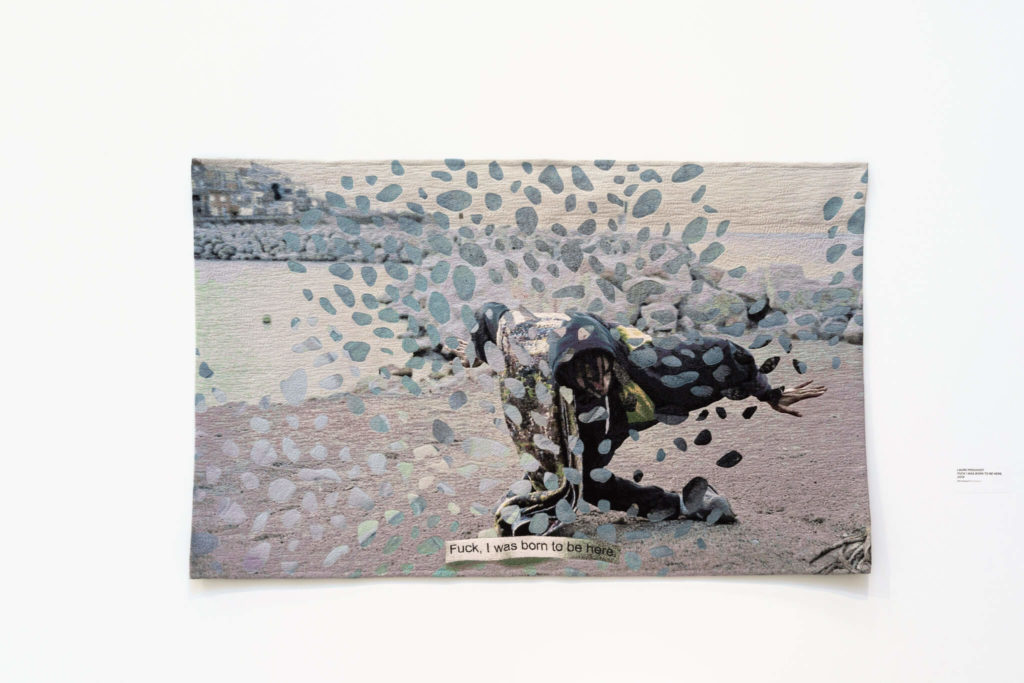

The dense, multi-layered dramatic composition is open for the audience to interpret for themselves in the context of the space.

Raphaela Vogel combines different, often contradictory media and art genres in a virtuoso manner. Her installations bring together objects and sculptures with videos in which she often appears herself, sings or plays the piano. Painting, collages and assemblages also form part of her work. However, her great strength lies in staging complex dramatic compositions in space in which narratives emerge between media stations with sculptural elements. Surrounded by these often exuberant installations, visitors find themselves in a dream world: all the elements seem to belong together although they do not form a logical or linear storyline.

The physical or visible presence of artists in their own works has played an important role in the visual arts since the 1960s. Female artists in particular have used performance art, videos and photography to liberate the female body from its role as a passive object in art. The contemporary generation of artists has long since accepted this understanding of their own role that conceives it within a pluralism of possibilities, and this can also be felt in Raphaela Vogel’s work.

In the video installation Tränenmeer, the artist appears in a bright pink dress. The viewer sees her, surrounded by raging waves and foaming surf, as she stands barefoot on a rock playing an accordion. The artist filmed herself using a drone with a 360-degree camera angle; as a result of this, the video seems to inescapably pull the viewer in. The image is overlaid with a haunting soundtrack formed of different layers: a baby’s cry, the sounds of a video being cut, the artist’s own piano improvisations, a clock ticking and the song Ich hab keine Angst (I Am Not Afraid) by the singer Milva. It also quotes the famous “fear of death scene” from Heinrich von Kleist’s play The Prince of Homburg.

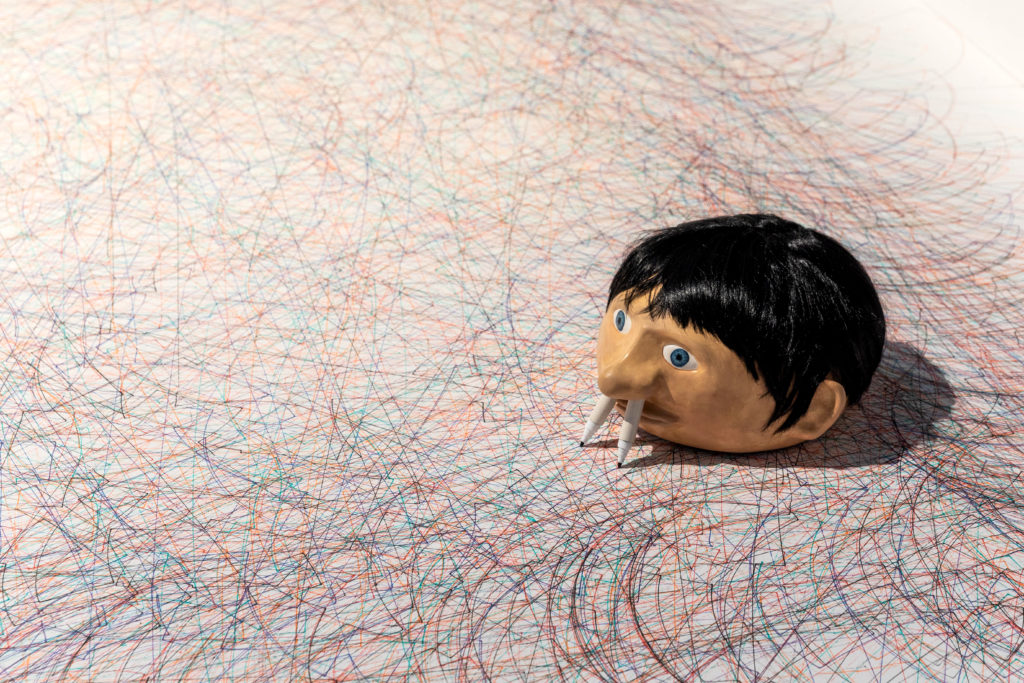

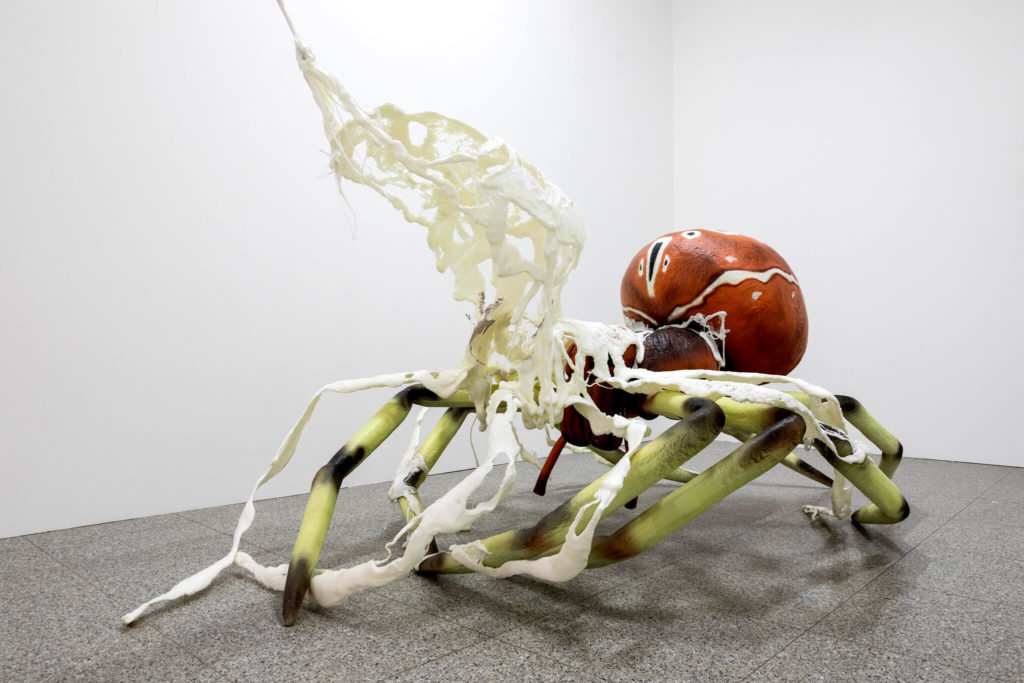

Fear and exclusion dominate the images and sounds. Their multiple layers accentuate rather than diminish their intensity. The virtual, cinematic sphere becomes merged with the physical sphere of the arranged space and objects. As the first work in the presentation and its centrepiece, Tränenmeer sets the atmosphere and the context of the works to which Raphaela Vogel relates it. For the sculpture Puppenruhe, she has hung a bundle of dolls from the centre of a truss structure so that they form a cluster of small, lifeless bodies. When the dolls are linked to the sound of a baby crying and to the neighbouring sculpture of an enormous tarantula, a mentally complex assortment of incongruous elements is formed. The motif of the spider is notoriously feared and also always has female connotations. Raphaela Vogel relates her own identity to this with humour and irony by invoking the tarantula.

The dense, multi-layered dramatic composition is open for the audience to interpret for themselves in the context of the space. Its fullness, however, is not based on a horror vacui, but rather on a deliberate artistic intention. Settings that expand into the space create proximity between the visitor and the works. This closeness runs counter to the impulse to distance oneself. The space is occupied completely – physically, acoustically and mentally. A densely woven web of references unfurls like conceptual threads between the works and seems to draw the visitor in closer and closer.

Johanna Adam

Raphaela Vogel grew up in Nuremberg, where she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, and later at the Städelschule in Frankfurt.